Dear Investor

General Market Overview

Market participants are currently highly focused on the words and actions of the world’s central banks. One of the Group of Seven (G7) central banks whose activities are being closely scrutinised is the Bank of Japan (BoJ). The Japanese Yen has weakened significantly compared to the United States (US) Dollar, which has far more impact on global markets than might be initially assessed.

In times of currency weakness, the BoJ would ordinarily raise interest rates to protect the currency. However, the Japanese debt-to-Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio is currently at 264%, making meaningful interest rate increases “unaffordable”.

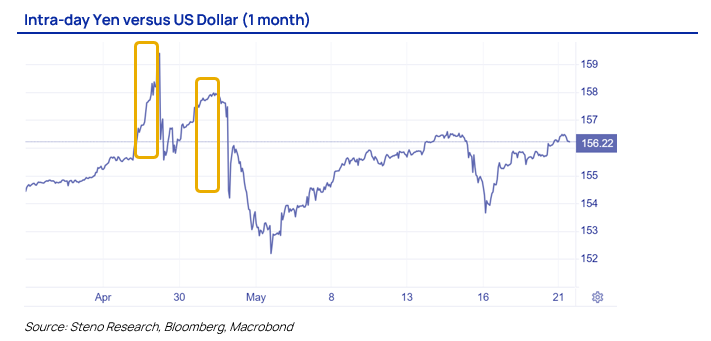

Japanese 10-year Government Bond yields have been rising in anticipation of a rate increase, and while still low in global terms, they are currently at their highest level since 2013. However, what has caused the most speculation is the suspicion that the BoJ intervened in the currency markets at the end of April and again in early May.

When the Yen hit the intra-day 160 level at the end of April (a 34-year low), there was a sharp reversal, and another sharp reversal was seen again in early May. There has been no confirmation from the BoJ or the Japanese Ministry of Finance (MOF) regarding the intervention, but the moves in the market and what has been assessed as “changes” in the MOF accounts point to intervention.

When central banks intervene in markets, several mechanisms can be used. There can be direct intervention by the bank where they either buy or sell their domestic currency using their foreign reserve holdings. Central banks can also use indirect intervention in the form of a “rate check” with significant currency dealers, which involves enquiring about Foreign Exchange (FX) rates to signal intention and influence the market. Frequently, they operate through a proxy, namely domestic banks acting as intermediaries buying and selling foreign currency.

Historically, a weaker Yen has been seen as positive for Japanese exporters, but current concerns are over increasingly expensive imported raw materials and weaker domestic consumption. One of the primary drivers for the weakness of the Yen is the disparity between Japanese interest rates and those of the Eurozone, United Kingdom (UK) and US.

One of the interventions Japan may consider to support its currency is the sale of some of its US Treasury holdings. Of the major central banks, the BoJ is the largest foreign holder of US Treasuries with $1.1 trillion. If the BoJ, under the instruction of the MOF, begins to sell US Treasuries, effectively selling US Dollars to buy Yen, this will create a ripple effect in markets.

Firstly, if the BoJ becomes a seller of US Treasuries, there will be increased Treasury supply, and some other entity will need to be on the “other side” of such a material trade. Selling pressure on US Treasuries pushes down the price of Treasuries and consequently increases the yield. A rising Treasury yield at the very point when the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) may be poised to start reducing rates would create a fundamental misalignment in fixed income markets.

There is also a sentiment component to central bank actions. While the BoJ may choose to sell Treasuries for specific domestic currency reasons, any central bank reducing their holding of what is considered the world’s safe haven asset, will shift sentiment. A change in sentiment may cause other central bank holders to reduce some of their exposure, thus creating a self-reinforcing rise in Treasury yields.

After Japan, the next largest holder in US treasuries is China. Recently, China has been aggressively selling US Treasuries. The assertion is that the Chinese Government has been using the proceeds of their Treasury sales to buy gold and is trying to diversify its foreign holdings away from Treasury holdings.

It is geopolitically “interesting” that China is choosing to reduce or diversify its Treasury position even as the US moves closer to a potential reduction in interest rates, which would be positive for US Treasuries.

The Fed had its last meeting at the beginning of May, during which it kept the federal funds rate unchanged at 5.5% for the 6th month. In the meeting minutes, released on the 22nd of May, there is evidence that the Fed is adopting a “wait and see” approach. Inflation has fallen from the 8-9% year-over-year (y/y) highs seen in mid-2022, but at 3.4% y/y in April, it remains above the Fed-targeted rate of 2%.

A growing area of concern in the US is its debt-to-GDP ratio, which is currently 122%. While some may argue that high levels of government debt can be maintained and cite the level of Japanese debt-to-GDP, which has been above 200% for decades, there is an interest expense component to debt servicing. The outlay on debt servicing (net interest) over the past seven months of the US fiscal year has now surpassed the amount spent on national defence, Medicare (primarily for those over 65) and Medicaid (primarily for low-income individuals).

To manage the level of national debt, the US introduced the concept of the “debt ceiling” in the Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 to manage wartime borrowing. Since then, the debt ceiling has been revised over 78 times to accommodate rising debt. No administration has ever reduced the debt ceiling, but the concept has undoubtedly created congressional theatrics over the years.

Currently, the debt ceiling has been suspended until the 1st of January 2025, which means that until that point, there will be no upper limit on governmental borrowing. US national debt reached $34.6 trillion in April, the highest level on record. The absolute magnitude of the debt and higher interest rates make that debt expensive to service. Ironically, the US Government would love the Fed to commence a reduction in the federal funds rate to reduce the cost of its borrowing.

General Conclusion

Central banks’ policies will undoubtedly be pivotal in shaping market trajectories over the coming months. An interesting metric representing global interest rates is the weighted global policy rate, which is currently 7.2%. Usually, the Fed would lead a broad shift in monetary policy, but currently, it is maintaining its cautious “wait and see” approach, which reflects the delicate balance between inflation curtailment that remains above the intended inflation target and the high national debt burden.

Swiss, Swedish, Czech and Hungarian central banks have reduced the cost of borrowing this year in response to falling inflation, and the European Central Bank (ECB) appears likely to be the first major central bank to cut rates in June. Eurozone inflation has fallen from above 10% at its peak in 2022 to a nearly three-year low of 2.4% in April, giving the ECB some leeway to start interest rate reductions. With an election now scheduled for the 4th of July in the UK, the Bank of England will likely reduce rates at its July meeting.

There is still much uncertainty in the macroeconomic environment, and patience and caution are required to assess and take advantage of shifting global capital flows arising from interest rate differentials.

10 June 2024

Comments